Pacemaker

A pacemaker is a small device that's placed (implanted) in the chest to help control the heartbeat. It's used to prevent the heart from beating too slowly. Implanting a pacemaker in the chest requires a surgical procedure.

A pacemaker is also called a cardiac pacing device.

Types

Depending on your condition, you might have one of the following types of pacemakers

- Single chamber pacemaker. This type usually carries electrical impulses to the right ventricle of your heart.

- Dual chamber pacemaker. This type carries electrical impulses to the right ventricle and the right atrium of your heart to help control the timing of contractions between the two chambers.

- Biventricular pacemaker. Biventricular pacing, also called cardiac resynchronization therapy, is for people who have heart failure and heartbeat problems. This type of pacemaker stimulates both of the lower heart chambers (the right and left ventricles) to make the heart beat more efficiently.

Types

Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy is a procedure to implant a device in the chest to make the heart's chambers squeeze (contract) in a more organized and efficient way. Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) uses a device called a biventricular pacemaker — also called a cardiac resynchronization device — that sends electrical signals to both lower chambers of the heart (right and left ventricles). The signals trigger the ventricles to contract in a more coordinated way, which improves the pumping of blood out of the heart. Sometimes the device also contains an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), which can deliver an electrical shock to reset the heartbeat if the heart rhythm becomes dangerously irregular.

Why it's done

Cardiac resynchronization therapy is a treatment for heart failure in people whose lower heart chambers (ventricles) don't contract in a coordinated fashion. It's frequently used for people who have heart failure and a condition called left bundle branch block or for people who are likely to require cardiac pacing due to low heart rates If you have heart failure, your heart muscle is weakened and may not be able to pump out enough blood to support your body. This can be worsened if your heart's chambers aren't in sync with each other. Cardiac resynchronization therapy may reduce symptoms of heart failure and lower the risk of heart failure complications, including death.

Risks

All medical procedures come with some type of risk. The specific risks of cardiac resynchronization therapy depend on the type of implant and your overall health.

Complications related to cardiac resynchronization therapy and the implantation procedure may include:

- Infection

- Bleeding

- Collapsed lung (pneumothorax)

- Compression of the heart due to fluid buildup in the sac surrounding the heart (cardiac tamponade)

- Failure of the device

- Shifting of device parts, which could require another procedure

What you can expect

Cardiac resynchronization therapy requires a minor surgical procedure to implant a device in the chest. You'll likely be awake during the procedure, but will receive medication to help you relax. The area where the pacemaker is implanted is numbed. The procedure typically takes a few hours. During surgery, insulated wires (leads, also called electrodes) are inserted into a major vein under or near the collarbone and move to the heart using X-ray images as a guide. One end of each wire is attached to the appropriate position in the heart. The other end is attached to a pulse generator, which is usually implanted under the skin beneath the collarbone.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy devices include:

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy with a pacemaker (CRT-P). The device used for cardiac resynchronization therapy has three leads that connect the pacemaker to the right upper chamber of the heart (right atria) and both lower chambers (ventricles).

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy with a pacemaker and an ICD (CRT-D). This device may be recommended for people with heart failure who also have a risk of sudden cardiac death. It can detect dangerous heart rhythms and deliver a stronger shock of energy than a pacemaker can deliver. This shock can reset the heartbeat.

You'll usually stay overnight in the hospital after cardiac resynchronization therapy. Your health care provider will test your device to make sure it's programmed correctly before you leave the hospital. Most people can return to their usual activities after a few days, although driving and heavy lifting might be restricted for a time.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs)

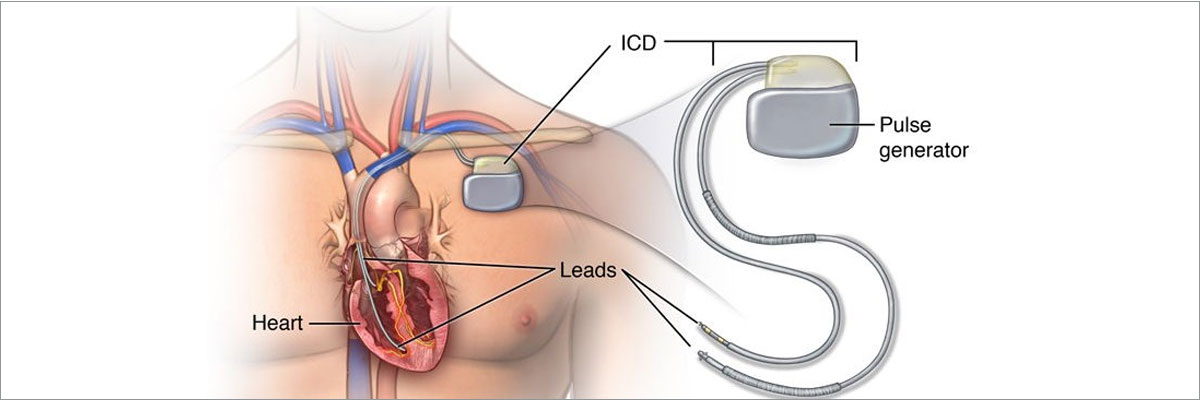

An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is a small battery-powered device placed in the chest to detect and stop irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias). An ICD continuously monitors the heartbeat and delivers electric shocks, when needed, to restore a regular heart rhythm.

You might need an ICD if you have a dangerously fast heartbeat that keeps your heart from supplying enough blood to the rest of your body (such as ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation) or if you are at high risk of such a heart rhythm problem (arrhythmia), usually because of a weak heart muscle.

An ICD differs from a pacemaker — an implantable device that can prevent dangerously slow heartbeats.

Types

An ICD is a type of cardiac therapy device. There are two basic types:

- A traditional ICD is implanted in the chest, and the wires (leads) attach to the heart. The implant procedure requires invasive surgery.

- A subcutaneous ICD (S-ICD) is another option that's implanted under the skin at the side of the chest below the armpit. It's attached to an electrode that runs along the breastbone. An S-ICD is larger than a traditional ICD but doesn't attach to the heart.

Why it's done

An ICD constantly monitors for irregular heartbeats and instantly tries to correct them. It helps when the heart stops beating effectively (cardiac arrest). Your health care provider may recommend an ICD if you've had signs or symptoms of a certain type of irregular heart rhythm called sustained ventricular tachycardia, including fainting. An ICD might also be recommended if you survived a cardiac arrest. Other reasons you may benefit from an ICD are:

- A history of coronary artery disease and heart attack that has weakened the heart

- An enlarged heart muscle

- A genetic heart condition that increases the risk of dangerously fast heart rhythms, such as some types of long QT syndrome

- Other rare conditions that may affect the heartbeat

A health care provider may recommend an S-ICD if there are structural defects in the heart that prevent attaching wires to the heart through the blood vessels.

Risks

Possible risks of having an ICD implanted include

- Infection at the implant site

- Swelling, bleeding or bruising

- Blood vessel damage from ICD leads

- Bleeding around the heart, which can be life-threatening

- Blood leaking through the heart valve (regurgitation) where the ICD lead is placed

- Collapsed lung (pneumothorax)

- Movement (shifting) of the device or leads, which could lead to cardiac perforation (rare)

How you prepare

Before you get an ICD, your health care provider will order several tests, which may include:

- Electrocardiography (ECG or EKG). An ECG is a quick and painless test that measures the electrical signals that make the heart beat. Sticky patches (electrodes) are placed on the chest and sometimes the arms and legs. Wires connect the electrodes to a computer, which displays the test results. An ECG can show if the heart is beating too fast, too slow or not at all.

- Echocardiography. This noninvasive test uses sound waves to create pictures of the heart in motion. It shows the size and structure of the heart and how blood is flowing through the heart.

- Holter monitoring. A Holter monitor is a small, wearable device that keeps track of the heart rhythm. It may be able to spot irregular heart rhythms that an ECG missed. You typically wear a Holter monitor for 1 to 2 days. Wires from sensors on the chest connect to a battery-operated recording device carried in a pocket or worn on a belt or shoulder strap. While wearing the monitor, you may be asked to keep a diary of your activities and symptoms. Your health care provider will usually compare the diary with the electrical recordings and try to figure out the cause of your symptoms.

- Event recorder. If you didn't have any irregular heart rhythms while you wore a Holter monitor, your health care provider may recommend an event recorder, which can be worn for a longer time. There are several different types of event recorders. Event recorders are similar to Holter monitors and generally require you to push a button when you feel symptoms.

- Electrophysiology study (EP study). The health care provider guides a flexible tube (catheter) through a blood vessel into the heart. More than one catheter is often used. Sensors on the tip of each catheter send signals and record the heart's electricity. A health care provider uses this information to identify the area that is causing the irregular heartbeat.

What you can expect

Before the procedure

If you're having an ICD implanted, you'll likely be asked to avoid food and drinks for at least 8 hours before the procedure. Talk to your health care provider about any medications you take and whether you should continue to take them before the procedure to implant an ICD.

During the procedure

A health care provider will insert an IV into your forearm or hand and may give you a medication called a sedative to help you relax. You will likely be given general anesthesia (fully asleep). During surgery to implant the ICD, the doctor guides one or more flexible, insulated wires (leads) into veins near the collarbone to the heart using X-ray images as a guide. The ends of the leads attach to the heart. The other ends attach to a device (shock generator) that's implanted under the skin beneath the collarbone. The procedure to implant an ICD usually takes a few hours. Once the ICD is in place, your doctor will test it and program it for your specific heart rhythm needs. Testing the ICD might require speeding up the heart and then shocking it back into a regular rhythm. Depending on the problem with the heartbeat, an ICD could be programmed for:

- Low-energy pacing. You may feel nothing or a painless fluttering in your chest when your ICD responds to mild changes in your heartbeat

- A higher energy shock. For more-serious heart rhythm problems, the ICD may deliver a higher energy shock. This shock can be painful, possibly making you feel as if you've been kicked in the chest. The pain usually lasts only a second, and there shouldn't be discomfort after the shock ends.

Usually, only one shock is needed to restore a regular heartbeat. Some people might have two or more shocks during a 24-hour period.

Having three or more shocks in a short amount of time is called an electrical or arrhythmia storm. If necessary, the ICD can be adjusted to reduce the number and frequency of shocks. Medications may be needed to make the heart beat regularly and decrease the risk of an ICD electrical storm

After the procedure

You'll usually be released on the day after the ICD procedure. You'll need to arrange to have someone to drive you home and help you while you are recovering. The area where the ICD is implanted can be swollen and tender for a few days or weeks. Your health care provider might prescribe pain medication. Aspirin and ibuprofen aren't recommended because they may increase the risk of bleeding. You'll usually need to avoid abrupt movements that raise your left arm above your shoulder for up to eight weeks so the leads don't move until the area has healed. You may need to limit your driving, depending the type of ICD received. Your health care provider will give you instructions on when it's safe to return to driving and other daily activities.

For about four weeks after surgery, your health care provider might ask you to avoid:

- Vigorous, above-the-shoulder activities or exercises, including golf, tennis, swimming, bicycling, bowling or vacuuming

- Heavy lifting

- Strenuous exercise programs

Your health care provider will probably tell you to avoid contact sports indefinitely. Heavy contact may damage the device or dislodge the wires.